Writers’ Cramp

Nobody writes much anymore. I’m not talking about novels or short stories or how-to-make-a-million-dollars-while-you’re-getting-your-nails-done books. I’m talking about writing –the physical act. WITH a pen or pencil (or crayon.) ON a piece of paper. TO communicate.

We have other, less cumbersome means.

The Three Rs of fundamental education have been on thin ice for a while, with “‘rithmetic” being the first to fade. We watched it go and some of us (let’s be honest) cheered for its departure as it went. Then “reading” began morphing to listening and watching (the side, we must admit, of a very slippery slope), and now “writing” seems to be hanging on by a fraying thread. We still communicate via text --aka the printed word—but we do it mostly on a keyboard, usually with our voices or our thumbs. We rarely write. While words remain our cognitive carriers conveying information, the way we make them has mutated.

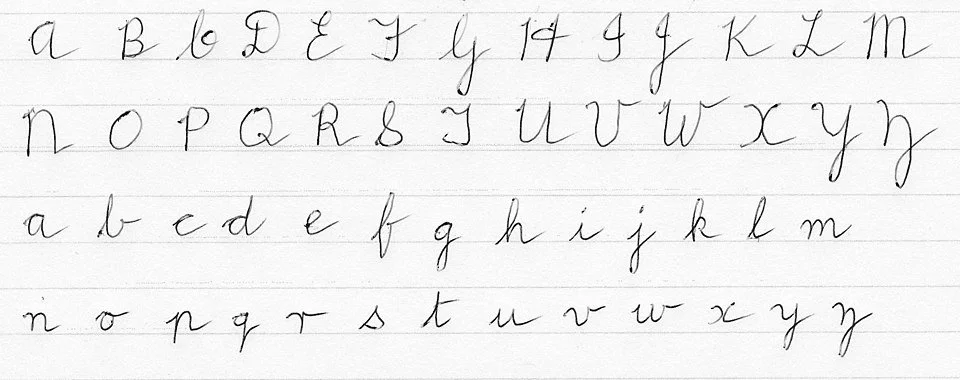

Source: PracticalPages — (CC by SA-4.0)

“Change is the only constant,” said a sage estimated to have walked the earth some 500 years before Jesus did. Heraclitus professed a truth the world still thumps us on the head with every day.

But, I wonder, “Have we really thought about this one? Do we really want to be a people who can’t (and I mean can’t, not don’t) make words with our hands?”

Years ago, somewhere between the formal education of my children and the respective births of theirs, cursive writing fell off the edge of a cliff and died. Schools removed it from the curriculum, so teachers stopped teaching it. As a result, the graduates of the next decade and beyond won’t be able (unless their parents vow to teach them) to read or write longhand. Words with flowy connected letters, some slanting poetically right, some leaning awkwardly left will get harder and harder and harder to find. And next to impossible to decipher. The art of handwriting has been lost. We swapped it for efficiency.

So much was given away in that trade.

Writing, the act of making letters that spell words that then form sentences --a physical manifestation of our thoughts-- is self-expression in and of itself. Penmanship, whether small and tight or large and loopy, is like a DNA molecule let loose in the air. How the lines look on the surface where we draw them becomes a part of our individual je ne sais quoi. We know handwriting the way we know the lilt of a laugh or the scent of hair. It’s revelatory. Our script sets us apart from one another. Without it we are one step closer to all being more the same.

One morning this past week while glancing at the “bombshells” and alerts of “breaking news,” a headline caught my eye. It read: “AI entrepreneur proclaims in Ted Talk that our grandchildren will be the last generation to read and write.” I swiped up with my thumb, per habit, almost as I read it, but then froze for a beat before scrolling somewhat frantically back down to re-read. The irony of ironies—a dinosaur on the edge of extinction using a skill to try to figure out why said skill will not be needed anymore. I clicked on the article to confirm my understanding. My eyes had not betrayed me. The headline said what I thought I read.

The last to read or write???

“How does a world work without words?” I said aloud to no one in the room. And then a better question, “Why would we want it to?”

Curious and deeply bothered, I typed “YouTube” in the search bar, then the key words “AI” and “read and write” in the box by the tiny magnifying glass. A man named Victor Riparbelli dressed in everyman all black, popped up on the screen with “TED” behind him in gigantic neon orange. He opened with a contrarian’s grin and the sentence that had punched me in the gut.

Then he began to make the case for a future full of AI.

I get it. I’m amazed at the things artificial intelligence can do. Clearly, those who don’t learn to use it will get left behind in a cloud of dust. Its capacity is incomprehensible and when used responsibly it can emphatically impact our world in a positive way. But purporting that reading and writing are skills that no longer serve us is more than a Gumby stretch.

I wish I could insert in Victor’s slide show of avatars and graphs, a birthday card signed by my granny, a handwritten letter on a faded yellow piece of blue-lined paper from my dad, the scripture in my mother’s penmanship engraved in weathered wood that hangs above my bed.

If I could, it might change the tenor of his message. At the least, his opening line. And he probably wouldn’t even care. He’d be too busy reading the teleprompter to notice.